Strange Days

Two birds and a bag full of stones

02 11, 09

It had been a long walk through the Shropshire hills in search of fossils and, with a good morning’s work completed and a bag full of rocks, I came down through the contours to Ludlow in search of a pub lunch.

Checking the map, I noticed a path beside an interesting looking woodland stream that was only slightly out of the way between fossils and lunch. To fill the miles I decided to do a spot of birdwatching on my way down and was looking forward to a light hike along it in search of Cinclus cinclus - the Dipper - a small brown bird that looks somewhat like a stunted, barrel-chested Blackbird with a white bib. Dippers are tenacious birds that often perch on rocks in the middle of fast-flowing shallow streams with their tails cocked like oversized Wrens. They feed by diving and swimming - even walking - underwater to catch aquatic invertebrates; at least, that’s what I’ve surmised from the bird books because, in all my years of watching, I’ve never actually seen one.

His one-man mission to spot our feathered friends, identify and then loathe them deeply seemed to be going well.

Despite what the field guides may tell you, the most common appearance of a Dipper is as a line drawing on a ‘context board’ erected by the river’s edge - those mounted information panels that feature paintings of bucolic loveliness, of habitats teeming with biodiversity, the preferred modern term for ‘life’. The boards are usually installed after a programme of works to dredge the last few shopping trolleys out of a river and present an optimistic vision of a habitat created by a partnership of organisations - organisations with striking logos designed to fit along the bottom of a context board. This particular panel was illustrated with an artist’s impression of what it would look like if all the interesting organisms from thirty miles around were condensed into a 300 yard stretch of river. I’ve long realised that anywhere that you can hear the white noise rush of a weir you’ll see a Dipper on a nearby context board and absolutely none in the river.

Moving on from the board, I scanned the river itself to no avail and decided to walk along the river a while. It wasn’t long before I saw someone else along the path, binoculars to his eyes, apparently studying a Mallard on the bank. I was a long way from home and looking for something specific, so what better than a local birdwatcher happy to share his insight into the birds on his patch? I made my way over and asked him if he knew of any Dippers on the river. It wasn’t long before I realised that I was talking to someone I now regard to be not only the world’s most unsuccessful birdwatcher, but - on account of his slightly swivel-eyed comportment - possibly its most drunken one as well.

He was almost completely unintelligible, except for the occasional ornithological English noun forming the victorious crescendo of an otherwise unfathomable sentence, its precise meaning slurred away like mud off a boot.

“Hrrurr gretsch pfftdf, Wagtail, mrmpgghaw (cough) azzerbunmhher, Swan”, was the rough gist of his part of the conversation which, at one point, inexplicably veered into “hhrghnngh wozzun hang glider” as he pointed at a passing microlight in the sky.

Joining the Dipper, between achingly rare orchids and damsel flies, a Heron and Mute Swan on the context board was the ubiquitous Mallard, a species that my new friend was keen to tell me his opinion of. After about five minutes wishing I was anywhere else but there, my ears had at last started to become accustomed to the drawl of drunken expletives and general ill-will towards the world in general and winged creatures in particular: “Them ducks, frawghhhar, gnmmph vicious bastards, you harrrrunt to look out for them.”

It had started to rain by this point, but the inebriated aviphobe was in full bird hating mode; it turned out that he recoiled from blackbirds, swallows and wagtails also - their specific crimes were not spoken of, but he despised them all the same. His one-man mission to spot our feathered friends, identify and then loathe them deeply seemed to be going well. He was just raising ire at pigeons and pouring scorn on crows when he paused for a moment and asked, “You RSPB, then?” Surprised and, indeed, in fear of being branded a collaborator, I assured him that I wasn’t. Mellowing a little he explained that he hadn’t seen a Dipper for years, which is probably just as well for the Dipper.

I pulled myself away, leaving him on the river bank, wandering away as nonchalantly as I could - at one point, I had fantasized about throwing some of my fossils at him and legging it down the path. The last I saw of him, he was chasing a duck.

Comments

Twitchers get their bird

12 03, 09

I’ve not long arrived in East Coker, two miles south west of Yeovil in Somerset – and have only managed to raise my binoculars for the fourth time – when a man in his mid-thirties marches as briskly from his car as his arsenal of optical equipment allows and asks me, “Is it showing?”

“It’s showing well,” I offer, in the manner of a Cold War era exchange of code words in the vicinity of an East German dead letterbox, but he hardly needs to be told because all of us, to a man, are staring so hard at a shed roof I fear we may burn a hole in the felt.

The formalities over, I give him the benefit of my considerable insight into the matter, gleaned from four or five minutes of intensive experience as a twitcher.

“It's nipping in and out of that Leylandii”, I tell him and after an appreciative nod, I lose him to the lure of a small slate-grey bird hopping about a shed roof.

Twitchers – the paramilitary wing of the birdwatching community – seem to exchange all their information in these urgent, staccato bursts. Dedicated to ticking off as many species as their leisure hours permit, they have evolved an efficient shorthand that sums up the facts in short order and, in this case, the facts are that there are half dozen of us standing on a driveway in a leafy village close and we are all here staring at a Dark-Eyed Junco – a mega-rarity, in birding parlance – which has found its way from North America to the roof of a garden shed in Somerset.

The shed’s custodian for the day is Stephen Tervit, who is looking after his parents’ home while birders, who have come from as far afield as Leicester and Shropshire, come and go all day. It turns out that there are another half a dozen of them sitting in the Tervit conservatory watching the Leylandii like mildly peckish Sparrowhawks. A number of them troop out with impossibly large spotting scopes and telephoto lenses and exchange observations about the bird’s feeding behaviour as they sit on the front step putting on their boots. Everyone is animated and affable – pleased, as one of them remarks, with “an excellent garden twitch”. A little donations tin on the kitchen table proves they are obliging as the bird is, having collected over £200 for the RSPB.

Tervit appears briefly at the door to tell us the form for the day – it seems as though we’ll all get a chance to do some armchair birdwatching sooner or later. A life-long birder himself, he happened to notice the Dark-Eyed Junco after filling the bird feeders in his parents’ garden and recognised it instantly, having seen the species on a holiday in the States, where they are abundant. A neighbour, another birder, put out the news on the twitching grapevine – until the 1990s an informal collection of public telephones in pubs near twitching hotspots, but now a 21st century network of web sites, text messaging and pager services. By the end of the first day, Tervit says, around fifty people had come to have a look. At least as many arrived the next day and now, on the third, I’ve seen around twenty birders in the hour or so I’ve been here.

“There was one earlier this year in Dungeness, so a lot of the more serious twitchers who saw it might not make the journey for another”, says Tervit but notes with pride that, “this one’s showing better, according to some folk”.

The Junco itself is variously described as an American Sparrow or Bunting, but at first sight reminds me more of a kind of monochrome Robin. It appears to be in very good health and, despite being various shades of grey with a dull pink beak it’s undeniably stunning. It probably found its way to Somerset after being blown off course during its autumn migration and, according to Tervit, “may even have finished its journey on a ship”.

The flow of birders continues on into the second hour and I’m aware that many of the people I arrived with have long since left. Having watched and ticked, the twitcher’s dilemma is what to do with it. The answer is simple: apparently, there’s an even rarer bird about that needs attending to – a Steppe Grey Shrike has made it from Siberia to Lincolnshire.

After years of birding resisting the temptation to turn twitcher, I’m now hopelessly hooked. As I wait for a taxi to take me to my train, yet more birders turn up. One, a middle-aged man in a sports car, leans out of his window to ask where the Junco is. After some directions, he turns to the real matter in hand. “Is it showing?”

“It’s showing well”.

The Short, Fat Man of Wilmington

08 01, 09

Eventually, I discover how to avoid the worst of it by lying down on a low bank that faces the Long Man of Wilmington – the fabulous, 230 foot-high hill figure on the South Downs and the reason why both the car park and I are here in the first place.

I become the damp and dumpy simulacrum of the giant on the hill - the Short, Fat Man of Wilmington (Car Park) - and just lie there for half an hour, gazing up at my brother on the aptly named Windover Hill, his head in the low clouds that lumber over the South Downs.

I am here for Lughnasadh - pronounced loo-na-sa - an important date in the celtic year, a harvest thanksgiving roughly approximate to Lammas, the Anglo-Saxon and Christian festival of the first-ripening fruits. Of all days, today does not feel like the end of summer and I wonder how many will attend.

I need not have worried. Around forty-five people gather in the car park and begin to make their way up the hill, among them Dave and Cerri, the facilitators of the druid group that is holding today’s open ritual - Anderida Gorsedd. The number of people here is a tribute to the group who have been holding open rituals here, no matter what the weather, since Spring 2000 - this being the 76th such gathering. But Dave, a lion of a man who has the aura of a congenial giant about him, nevertheless seems a little troubled by person number 46, me.

“People have lost their jobs before, after being identified in the local papers as pagans or druids”, he says and, indeed, it’s not the first time that I’ve heard this, “so we’re not seeking publicity.”

As I chat with Cerri - a jovial soul in a jumper emblazoned with a huge sun motif - Dave wanders off to greet some old friends but is soon back with a relaxed smile on his face and hurtles towards me with arms outstretched.

“Oh and welcome, of course. You are going to join in with the circle, aren’t you?”

“I wouldn’t miss it for the world”, I tell him.

The forty-five of us gather halfway up the hill on a wide, round, flat-topped hummock - which looks suspiciously as though it was built for this very purpose - just below the feet of the Long Man. I stand next to Sylvia, who tells me of her mother who had one brown and one blue eye and a witch-ish grey streak of hair from a young age. But despite that, Sylvia was still christened and it was only circumstances later in life that brought her into the Wiccan tradition. “Me and my husband both lost parents and we wanted to find something that brought us both happiness and this is what this is.”

At this point our conversation is rudely interrupted by the ritual we had come to participate in. Having attended similar events before, I’m looking forward to the singing, which is odd as I have an awful voice that I don’t usually like to bother others with. On a windy hillside, for some reason, I’m not so shy.

Pagans are the jazz musicians of the theological world, however. They like to improvise, throw in some bardic ad-libs or riff a little on poetry, so there’s no set pattern to rituals beyond opening and closing the circle, calling the elements and the hail and farewells. I admire this approach but - basically - bang goes the sing-song, leaving only the ‘awen’ to tackle, a kind of 15 second long ‘amen’ chanted three times after the druid’s prayer. It is unspeakably beautiful and fully justifies its billing as the breath from which inspiration flows. As the last chant tails off and all chances for me to find the right key evaporate, a sheep grazing on the Long Man bleats in perfect harmony.

The centrepiece of Lughnasadh is the symbolic sacrifice of John Barleycorn, the corn god. With his arms outstretched and fists clenched, a golden sickle is drawn across his throat. He falls to his knees and releases the ripe grain he holds in his hands. It’s hard-hitting stuff artfully done on a hillside, but that’s the essence of pagan life.

As the circle is closed, each direction is thanked in turn. Finally, we all face east and thank the gods of air, who respond by ripping the final hail and farewell from our mouths with a remarkable gust of wind. Hail and farewell indeed.

The Baptist’s Bonfire

21 10, 08

At the end of a long journey into Cornwall, crumpled into a corner of a train, I was longing to get out on the open moor. Aside from the cattle truck stylings of British rail travel, the journey only reinforces the impression that Cornwall is a very long way from anywhere. And, along with the promise of witnessing an event that, though once widespread, only occurs now in Cornwall, it is this remoteness that brings me here.

“Here” turns out to be somewhere between Penzance and Zennor in a field near the hamlet of Boswarthen which is, itself, to be found just off an isolated road north of Madron. Despite the abundance of placenames, each of which sounds like the grave syllables of a mumbled prayer, I am effectively bang-slap in the middle of nowhere.

I’m here for a bonfire, specifically a midsummer’s eve bonfire on top of a hill overlooking Mounts Bay – one of at least half a dozen such events arranged by local Old Cornwall Societies up and down the county. The guiding principle of these societies is to hold on to the old customs and keep them alive for the next generation – a process of ‘gathering the fragments’ of Cornish culture, language and traditions which has steadily grown in popularity over the years. Sure enough, the secluded lane quickly fills with parked cars as organisers and spectators turn up, almost all at once. People of all ages are here, from the local Young Farmers who are having a barbecue in the back of a horse box, to a strong contingent of senior villagers.

“Health and safety would probably want us to put up a barrier around that”, says Roy Matthews, Honorary Chairman of the Madron Old Cornwall Society, waving in the general direction of a 12 foot high pyramid of old pallets and fertiliser bags. “But the thing with a fire is that it’s hot, you see. Nobody’s going to be able to get anywhere near it once it’s lit.”

He goes on to explain some of the history of the bonfires. Thousands of years ago, animal sacrifices would be made on them. “Sometimes, they’d throw the odd criminal on”, says Matthews, with a playful gleam in his eye, “but now we throw a wreath on instead.”

By about 9 pm, around seventy people have crowded into the small field. The air is thick with the smell of the horse box burgers, dozens of conversations have coalesced into a soft murmur, at which point we are handed our photocopied song sheets – along with a steely warning to return them later. We are to be accompanied by the parish priest, the Rev. Tim Hawkins who, rather than appear here in an official capacity, has brought his viola along instead.

At first I mouth the words, like a self-conscious schoolboy in morning assembly, as I don’t wish to appear impolite, but I am eventually swept up in it all - the beautiful location, the camaraderie and the life-affirming spirit of a sing-along at 700 feet. Undaunted by my lack of vocal talent, I join in with Hail to the Homeland and Going Up Camborne Hill, Coming Down and my mind is elevated from its usual default settings. I have become one of them.

As night draws in, and with the final chorus of Trelawney still ringing in my ears, the ceremony begins in earnest with the reading of the prayer – first in Cornish, then English. When the ancient Celts were converted to Christianity, the fires were transformed, with the early Church’s usual resourcefulness, into celebrations of the Feast of St John the Baptist. As a result, every bonfire now has a benediction which includes a couple of priceless puns about “being lighted by Thy grace and fired with Thy love”.

After a brief explanation of the symbolism of the bouquet of herbs that are to be thrown in to the fire – in place of a local ne'er-do-well – and some words from the Master of Ceremonies, a man appears with a bottle of white spirit to set things off in style. It’s only moments before the pyre is blazing furiously away, its wild flames clawing at the inky blue-black sky. For all the layers of ceremony, etiquette, poetry and faith superimposed over the night, the fire itself is the focus and this is as it would have been for our ancestors, a celebration of summer through the building of a simulacrum of the sun itself.

Clinging onto those thoughts, I wind down the narrow lane home. A Cornwall Fire Brigade engine with sirens screaming and blue lights blazing appears from nowhere, heading in the direction of the flames I have left behind. For all the efforts of the organisers, it seems that the wild old and the ordered new Cornwall are yet to be reconciled.

Merry Meet Under a May Moon

21 09, 08

It’s not even closing time at the Red Lion in Avebury and there is already witchcraft afoot in the field next door. Nobody is in the least bit surprised and this alone speaks volumes about the interesting mix of characters you find in an average English village, except that Avebury is anything but an average village.

It stands in the centre of an enormous stone circle – fourteen times the size of Stonehenge – and arranged around the inner perimeter of a precipitous 4500 year-old ditch and bank. The great 17th century antiquary, John Aubrey put it best when he noted it ‘doth as much exceed in greatness the so renowned Stonehenge, as a cathedral doth a parish church’.

Leaving the pub, I venture out into this cathedral and notice the bob and swing of hand-held lanterns on the far side of a dark field punctuated with sarsen monoliths. Despite tonight’s full moon, slowly rising over the clutch of thatched cottages at Avebury’s centre, there seems precious little light about and I stumble over a short wall, up and down kerbs, over a stile and across rough ground, cursing the darkness with every step.

I have come to catch the Ogam Observance of the Full Moon – a druidic ceremony that marks the exact moment of the moon’s zenith. Tonight, the exact moment turns out to be just after three in the morning and though I am willing, my B&B is a mile up a road on which motorists observe only the reckless pursuit of Swindon, tending to drive in a manner that makes matters tricky for the hapless moonlit pedestrian.

Fortunately, I have met Gordon Rimes, a 61-year old Wiccan priest with a kindly avuncular manner and – as it turned out – a day job as a balloon artist of some standing. Gordon told me he’d be ‘doing something’ tonight – a pagan ritual known as an ‘Energy Raising Circle’ – and invited me to come along.

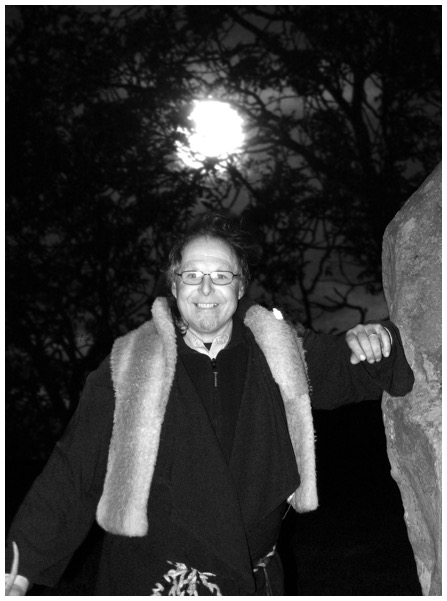

I stumble across the field and find Gordon resplendent in a long green robe and a fake fur jerkin laying out lanterns at the cardinal points of a small imaginary circle. A larger, wilder flame flickers in the centre and on the eastern side, two lanterns form a metaphorical doorway through which all exit and enter.

I say ‘all’, but there’s only two of them there – Gordon and a woman I didn’t quite catch the name of. I am invited to either remain on the periphery and watch, or join the circle and participate. I decide to join in.

Drawing an imaginary gateway on the side of the circle, Gordon invites me in. Immediately, the four elements are beckoned – by bellowing ritual jargon at them – to come and join us in the moonlight. We all join hands in the circle. Being British, I find that the novelty of holding hands with strangers is almost a religious experience in its own right and I begin to tingle for cultural reasons. We walk, gather pace, then run clockwise around the circle. The others begin to sing but I don’t know any of the words and have lost the tingle by the time we come to a halt.

After a moment of reflection, off we go again, wheeling around hand in hand, singing, invocations flung out into the night like bats lobbed from a fast car on a roundabout. In this flurry, Gordon mentions a horned god of some kind, but the moment to check we aren’t alluding to Satan is whipped away in frantic dance. The vortex grows wilder still, hands are released and we fizz around like unstable electrons. The circle is briefly chaotic and Gordon acquires a puckish effervescence in his eyes.

I’m not really given to singing and dancing in public – not even in a dark field with a limited audience, so I’m grateful as things settle down a bit and offerings are made, but even here there are surprises. When we met earlier, Gordon confessed that he doesn’t always play it by the book and some Wiccans probably take issue with his interpretations of pagan rituals.

His choice of offerings – traditionally cake and ale – could raise a pagan eyebrow or two. On the one hand, we drink mead from a chalice – which seems old-school-spiritual enough, even though Gordon boasts that he bought it in Morrisons for £3.74, but for ‘cake’, we pass around a bowl of ready salted crisps.

At almost midnight our hosts wind things up by scattering the remnants of crisps to the four elements and thanking them in turn – air, fire, earth and water – each to a chorus of ‘hail and farewell’. Final words are spoken – ‘merry meet and merry part and merry meet again’ – and we go our separate ways, a little lighter, under the watchful gaze of the still waxing moon.