Life Made the Mountain, the Mountain Came Alive.

04 03, 20 Filed in: Commissions | Katie Paterson

It seems odd to stand on a beach and tilt your head up for a view of the ocean floor, but that remarkable feat can be achieved on West Shore Beach at Llandudno. The cliffs and slopes that terminate each end of Ormes Bay are the petrified remains of a former sea floor - the bottom of a shallow sea, now long gone, that existed over 325 million years ago. This is not unusual; most mountains are made from sediments laid down in the ocean. What is special about limestone uplands like the Great and Little Orme, is that they were originally made a long way offshore. The sediment that created them did not come from the erosion of an earlier landmass; it was left by living organisms.

The uplands around Llandudno were laid down in a shallow tropical sea during the Carboniferous, a period of deep time that teemed with life. The southern shore of this ocean continually moved, with the sea periodically inundating and then receding over dense lowland rainforest where ancient dragonflies reached the size of seagulls and millipedes grew to one and a half metres long. Continual flooding of the forest floor left layers of dead plants collecting and compressing over millions of years to eventually form the coal seams of South Wales. Carboniferous means coal-bearing.

Like the coal seams to the south, the Carboniferous limestone around Llandudno is made of life itself. The Orme limestones were formed from the shells and exoskeletons of billions of brachiopods, crinoids and corals. When the limestones were first laid down, Wales was located along the equator and the climate was similar to the modern Bahamas. Britain also lay at the centre of a super-continent of all the world's land called Pangaea. In Pangaea, a walk from Llandudno to New York would have taken about a month, followed by a wait of around 330 million years.

As the continents crushed into one another for Pangaea's assembly, the Caledonides - a mountain range of Himalayan proportions - formed to the north eventually eroding down to the Scottish Highlands. It was during this period of mountain building that the Orme was uplifted. From the Promenade, you can even see the fold of the rock beds above the Grand Hotel and under the pylons of the cable car.

Mineral-rich water seeped into the fissures created as land was uplifted and rucked like a rug. Dissolved copper crystallised into ore known as malachite and enough of it would be extracted from the Great Orme mine during the Bronze Age to make at least ten million axe heads. The Orme was one of the largest industrial sites of the Bronze Age world.

In the shadow of the past's industry on West Shore Beach, pails of sand are temporarily installed in the form of five of the world's highest peaks, one for each inhabited continent. Next to the seeming permanence of the Great Orme, they are fragile structures against the sea, but every mountain eventually dissolves to an incessant and unfaltering tide - erosion now hastened and catalysed by acid rain, habitat loss, walking boots, tyres and over-grazing. Our mountains are fragile too.

In other parts of the world, mountains stand aloof. Wood smoke fills the valley floors, agriculture, industry and the material needs of people predominate below, while the mountain is the home of spirit, the mark of permanence, the symbol of calm. On the seaboard of Wales, it was reversed. The mountains were places of industry - of mines and quarries - while, in the valleys that met the shore, buckets and spades beside the seaside had an altogether different purpose to their mountain counterparts.

Much of that has been upended and usurped by technology, by modernity, by the blunt forces of economics and politics. The industrial mountain has become silent, even in the hubbub of its new appeal to tourism. But, within the projected spectacle of visitor centres and heritage attractions, we should take a longer view, not only at our own lives, but at the lives that made the mountain and the lives it created, enhanced and to which it added the illusion of permanence.

First commissioned for the artwork First There is a Mountain, by Katie Paterson

The uplands around Llandudno were laid down in a shallow tropical sea during the Carboniferous, a period of deep time that teemed with life. The southern shore of this ocean continually moved, with the sea periodically inundating and then receding over dense lowland rainforest where ancient dragonflies reached the size of seagulls and millipedes grew to one and a half metres long. Continual flooding of the forest floor left layers of dead plants collecting and compressing over millions of years to eventually form the coal seams of South Wales. Carboniferous means coal-bearing.

Like the coal seams to the south, the Carboniferous limestone around Llandudno is made of life itself. The Orme limestones were formed from the shells and exoskeletons of billions of brachiopods, crinoids and corals. When the limestones were first laid down, Wales was located along the equator and the climate was similar to the modern Bahamas. Britain also lay at the centre of a super-continent of all the world's land called Pangaea. In Pangaea, a walk from Llandudno to New York would have taken about a month, followed by a wait of around 330 million years.

As the continents crushed into one another for Pangaea's assembly, the Caledonides - a mountain range of Himalayan proportions - formed to the north eventually eroding down to the Scottish Highlands. It was during this period of mountain building that the Orme was uplifted. From the Promenade, you can even see the fold of the rock beds above the Grand Hotel and under the pylons of the cable car.

Mineral-rich water seeped into the fissures created as land was uplifted and rucked like a rug. Dissolved copper crystallised into ore known as malachite and enough of it would be extracted from the Great Orme mine during the Bronze Age to make at least ten million axe heads. The Orme was one of the largest industrial sites of the Bronze Age world.

In the shadow of the past's industry on West Shore Beach, pails of sand are temporarily installed in the form of five of the world's highest peaks, one for each inhabited continent. Next to the seeming permanence of the Great Orme, they are fragile structures against the sea, but every mountain eventually dissolves to an incessant and unfaltering tide - erosion now hastened and catalysed by acid rain, habitat loss, walking boots, tyres and over-grazing. Our mountains are fragile too.

In other parts of the world, mountains stand aloof. Wood smoke fills the valley floors, agriculture, industry and the material needs of people predominate below, while the mountain is the home of spirit, the mark of permanence, the symbol of calm. On the seaboard of Wales, it was reversed. The mountains were places of industry - of mines and quarries - while, in the valleys that met the shore, buckets and spades beside the seaside had an altogether different purpose to their mountain counterparts.

Much of that has been upended and usurped by technology, by modernity, by the blunt forces of economics and politics. The industrial mountain has become silent, even in the hubbub of its new appeal to tourism. But, within the projected spectacle of visitor centres and heritage attractions, we should take a longer view, not only at our own lives, but at the lives that made the mountain and the lives it created, enhanced and to which it added the illusion of permanence.

First commissioned for the artwork First There is a Mountain, by Katie Paterson

Comments

Reading the Landscape: The Village Pond

02 05, 14 Filed in: Countryfile | Reading the Landscape

In the opening decades of the twenty-first century, the village duck pond might seem like a quaint anachronism, a little out of step with modern life, perhaps, despite its obvious charms as a wildlife haven and somewhere to relax awhile. For all its modern serenity, however, the village pond was once a place where the scene would be far from quiet and the pond and its green would be at the very centre of village life. Perhaps hard to believe at this time of year, when the tadpoles begin to climb the slippery pole of survival and natural life flourishes all around them, but for their medieval builders, ponds were huge undertakings and aesthetics were probably the last things on their minds.

Like the village green it is part of, the pond is often common land, a communal facility for the use of the whole village. Historically the village pond is likely to have provided fish – pisciculture was conducted with great enthusiasm in the Middle Ages – and would have been also used for soaking cartwheels (to prevent them from shrinking), washing clothes and as a watering hole for cattle, either grazing on the green itself or providing water for itinerant droves on the move to market or up the valley for summer pasture.

Once those cattle were safely moved up to the downs, another kind of artificial pool, the dew pond, would come into its own. Chalk, limestone and sandstone are porous and, as a result, surface water is absent; dew ponds – sometimes known as mist or cloud ponds – are saucer-shaped circular pools up to eight feet deep at the centre and often constructed in a slight hollow on a hill top. They were made between September and April by touring workers – it would take four men four weeks to make a large dew pond.

Traditionally-made dew ponds are lined by puddled clay, though chalk can also be puddled by reducing it to a powder, adding water until it is the consistency of clotted cream, smoothing it out and letting it dry, whereupon it becomes completely impermeable and better suited to the task than the Portland cement sometimes used by modern contractors.

Once built, the pond is then – confusingly – not filled by dew (or mist) at all, but by rainfall, while the dew pond’s position in a slight hollow helps keep the water cool and reduces loss by evaporation.

Claims are made that the two dew ponds of Chanctonbury Ring on the South Downs in Sussex date back to the Neolithic, but the oldest recorded dew pond is Oxenmere on Milk Hill in Wiltshire, which is named in a Saxon charter of 825 CE/AD.

Reading the Landscape: Holloways

29 11, 13 Filed in: Countryfile | Reading the Landscape

Of all the various roads and paths that snake their way through the countryside – A roads, B roads, byways and bridleways – it’s interesting to note that some ways are invested with a little more romance than the rest and by some ways, I mean green lanes and holloways.

While ‘green lane’ is a catch-all for many different kinds of unsurfaced rural road or path – such as an old drove, a coffin road or a ridgeway – a holloway is a more specific term. It describes a sunken green lane, a track which was been worn down by the passage of thousands of feet, cartwheels and hooves over hundreds of years, even millennia. With the loosened soil subsequently washed away by the next downpour, the course of a holloway will often become more pronounced on the side of a hill because of the extra energy imparted by the surface water run-off.

Holloways are common in lowland Britain with the greensands of the southern counties – Wiltshire, the Weald and the Chilterns – being particularly suited for their formation, as is the old red sandstone of the Wye and Usk valleys of Wales and the Marches, while the new red sandstone of south and east Devon has splendid, deep lanes on its slopes.

Over time, as they are inscribed ever more deeply and the level of the lane lowers, they become more sheltered and trees arch over, creating a womb-like tunnel, an enclosed place of natural safety. So safe, indeed, that it’s only around this time of the year that the walls of foliage have died back enough to get into some old lanes, long-since-abandoned by changing patterns of passage over the land, bypassed in favour of a better route.

Where holloways have fallen into disuse for even longer periods, they can be discovered anew – many centuries after they were last followed – by tell-tale shallow linear grooves through fields or woodland, though check that it’s not a short stretch of long-forgotten park pale or a defensive ditch, both of which will be accompanied by a bank above the natural ground level.

Holloways have their own atmosphere, an unexpected quality which cannot be explained away purely in terms of the local topography or geology. As ancient routes, they are the perfect expressions of collective will, tracks which share a common origin with desire lines – those unpaved paths across city parks or shortcuts over open ground that urban planners never anticipated. As travelling long distances was more difficult in the past, the reasons were more keenly felt; every footstep has meaning on a pilgrimage and the burdens shouldered on a well-used coffin road were more than the purely physical.

Reading the Landscape: Trig Points

25 10, 13 Filed in: Countryfile | Reading the Landscape

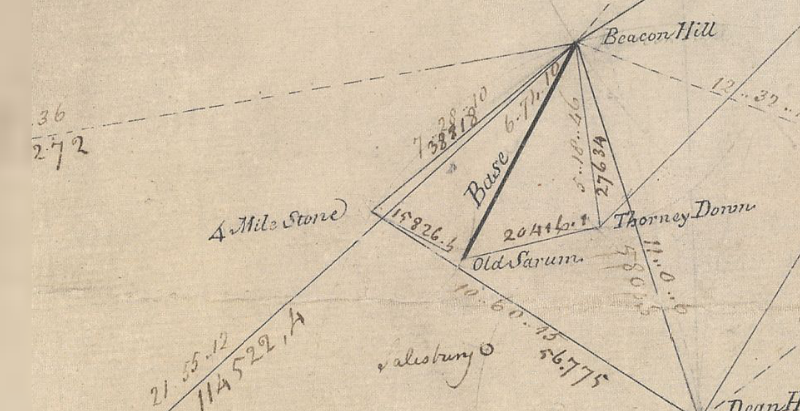

Just northeast of Old Sarum, the abandoned city that looms over younger, yet medieval, Salisbury, lies a monument important enough to be marked on Ordnance Survey maps, along with an intriguing inscription: ‘Gun End of Base’.

In many ways, it’s the most important point on the map, because if it wasn’t for Gun End of Base – actually the muzzle of a cannon buried vertically, business end up – there might not be a map at all. This is the spot where the first definitive mapping survey of Britain began in 1794, where initial measurements for the ‘principal triangulation of Britain’ were taken by Artillery man Captain William Mudge.

You can still see the snout of the cannon at Old Sarum, but the gun at Beacon Hill, 7 miles to the north where Mudge set his theodolite, was eventually replaced by a triangulation pillar, or trig point, 140 years later.

A small, tapered obelisk 4 feet tall and 2 feet square at the base, often found at the summit of a hill, the trig point is a welcome sight for walkers and climbers, although you don’t always need to scramble to the top of a draughty peak to bump into one; starting with Cold Ashby in Northamptonshire – in the middle of a rather flat field at SP644765 – there were around 6,500 built between 1936 and 1960, including one on the Little Ouse in Norfolk TL617897, a metre below sea level. Today, around 5,500 pillars remain at large, though only 110 remain in active service as part of a GPS-style network.

A familiar fixture in the British countryside since the OS built them to survey the country anew, the stability of trig points enabled surveyors to take very accurate measurements which allowed them to perform calculations that, in the trig point’s day, were accurate to 20 metres from one end of Britain to the other. Satellite technology has now improved that to just 3mm.

Trig points aren’t the only mapping artefacts you can discover in the field. Small metal plates marked with a broad arrow pointing up to a horizontal line, or ‘bench mark’, indicate a known height above sea level – and can be found on most pillars as well as the sides of churches, bridges and public buildings. They are joined by around half a million chiselled-out marks on walls all over Britain, which helped to define every last contour and spot height that appear on the map, often next to the triangular symbol that marks the trig point. And, as you catch your breath from the climb up to that pillar, you’ll see that if there’s one thing you can be sure of, it’s a fine view – of the next one.

Reading the Landscape: Deserted Medieval Villages

29 09, 13 Filed in: Countryfile | Reading the Landscape

The eternal peril of its pubs and post offices aside, it’s hard not to view the British village as something of an indestructible institution, but it wasn’t always such a permanent fixture and the threats that it faces now pale into insignificance next to the menaces of the middle ages, when entire communities could be smeared from the map on the say-so of just one person.

The ‘Medieval Village’ label on Ordnance Survey maps carries an inevitable presumption of plague, but the spectre of a multitude of whole settlements exterminated by the Black Death is an exaggeration. Conspicuously large churches, like the magnificent St Mary’s at Tunstead in Norfolk where construction work was halted by the Great Mortality (as it was known at the time) are perhaps better indicators of the plague’s effect; villages were certainly weakened and reduced, but they were not always completely extinguished.

The real menace of the middle ages – the agent of chaos that threatened communities up and down the land – turns out to be nothing more than the humble sheep. Innocuous and dim as individuals, in farmed flocks their role as woolly bailiffs was well-established before, and for centuries after, the Black Death left its mark.

Cistercian monks were among the first to farm sheep on the enclosed lands of evicted villages. The Cistercian craving for isolation found expression in the destruction of villages like Cayton and Herleshow in Yorkshire in the twelfth century, both given to Fountains Abbey in return for eternal salvation for their noble freeholders, while tenants suffered the temporal damnation of being forced to move on.

The Black Death would play its own merry part later. With a reduced working population demanding better terms, the manorial lords, perhaps inspired by the Cistercians, filled their lands with sheep. Wharram Percy in the Yorkshire Wolds, the most famous of Britain’s 3,000 abandoned villages, was finally cleared in the early sixteenth century and enclosure continued in England for another three hundred years. From the seventeenth century on, enclosure was increasingly for country house emparkment, where designers like Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown grazed on the profits of landscape enclosure in place of the sheep.

In Scotland, the ovine menace reared its ugly head once more in the infamous Highland Clearances of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Some of the most brutal of the clearances occurred at Boreraig and Suisnish on the north shore of Loch Eishort on Skye; families were forcibly evicted and sent packing, their homes burnt down. Geologist Archibald Geikie who happened to witness the eviction in 1853 described the cortege that led north along the track from Suisnish and the grief-laden wail echoing along the strath as a ‘prolonged note of desolation’.

The ‘Medieval Village’ label on Ordnance Survey maps carries an inevitable presumption of plague, but the spectre of a multitude of whole settlements exterminated by the Black Death is an exaggeration. Conspicuously large churches, like the magnificent St Mary’s at Tunstead in Norfolk where construction work was halted by the Great Mortality (as it was known at the time) are perhaps better indicators of the plague’s effect; villages were certainly weakened and reduced, but they were not always completely extinguished.

The real menace of the middle ages – the agent of chaos that threatened communities up and down the land – turns out to be nothing more than the humble sheep. Innocuous and dim as individuals, in farmed flocks their role as woolly bailiffs was well-established before, and for centuries after, the Black Death left its mark.

Cistercian monks were among the first to farm sheep on the enclosed lands of evicted villages. The Cistercian craving for isolation found expression in the destruction of villages like Cayton and Herleshow in Yorkshire in the twelfth century, both given to Fountains Abbey in return for eternal salvation for their noble freeholders, while tenants suffered the temporal damnation of being forced to move on.

The Black Death would play its own merry part later. With a reduced working population demanding better terms, the manorial lords, perhaps inspired by the Cistercians, filled their lands with sheep. Wharram Percy in the Yorkshire Wolds, the most famous of Britain’s 3,000 abandoned villages, was finally cleared in the early sixteenth century and enclosure continued in England for another three hundred years. From the seventeenth century on, enclosure was increasingly for country house emparkment, where designers like Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown grazed on the profits of landscape enclosure in place of the sheep.

In Scotland, the ovine menace reared its ugly head once more in the infamous Highland Clearances of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Some of the most brutal of the clearances occurred at Boreraig and Suisnish on the north shore of Loch Eishort on Skye; families were forcibly evicted and sent packing, their homes burnt down. Geologist Archibald Geikie who happened to witness the eviction in 1853 described the cortege that led north along the track from Suisnish and the grief-laden wail echoing along the strath as a ‘prolonged note of desolation’.